Refugees are seen either as criminals or saints.

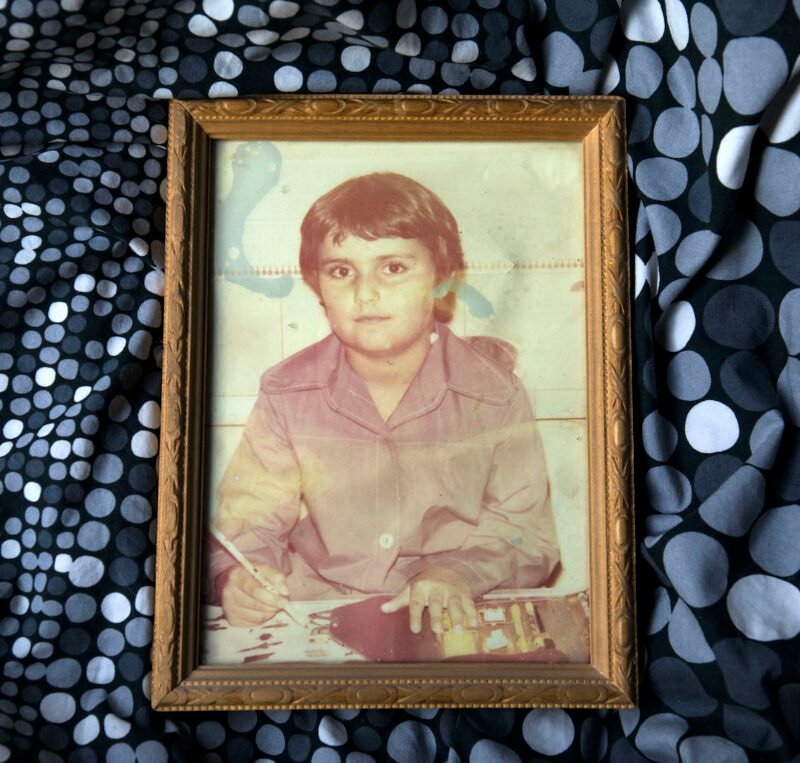

The bombing always happened at night and we used to hide in the bathroom because it was the safest place in our house. My parents slept on the floor, my brother in the bathtub and I slept on top of the washing machine. I stayed in Sarajevo for the first three weeks of the war and I clearly remember I was in a tea shop with my friends, when a group of men came in and started shooting at people. One morning my mother got a call from her friend, telling her buses were leaving the city, that there is a place for me on it, and that I had to get ready immediately. I was very aware of what was happening and when you’re in that situation and someone says leave, you listen.

It wasn’t a religious war, but religion was relevant because it helped divide the population and promote a sense of ‘belonging’ to one party which in turn promoted nationalism and got people to follow them. The religious aspect only really became apparent during the war, the division based on religion now is absurd.

The issues of eugenics weighed heavily during the war, if a Croatian woman married a Serbian man many people thought the children were dirty. Every racist claim in history applied to mixed marriages. My father is from Montenegro where there is a more Orthodox population, and my mother is Croatian from the border of BiH and Croatia. Politically my parents didn’t get along and while in Yugoslavia it wasn’t an issue because everyone had mixed families, we were made acutely aware of this during the war. It wasn’t a religious war, but religion was relevant because it helped divide the population and promote a sense of ‘belonging’ to one party which in turn promoted nationalism and got people to follow them. The religious aspect only really became apparent during the war, the division based on religion now is absurd. I didn’t believe in any of the factions, or the armies because they were also organised by nationality.

When I left, I couldn’t even say goodbye to my father and brother because they were out looking for food. There was a convoy leaving Sarajevo with women and children on board, my brother was only 15 at the time but even then, he wouldn’t have been allowed onto the bus because he was perceived as a man. I didn’t know where the bus was going, it was either to Belgrade or Spilt. I had this primal instinct that has nothing to do with being a teenager, in any other way I was a typical one – I would protest and question things, but when you’re at war and living on a washing machine you start to perceive and understand things through your instincts. We had no plans for the future; we were in the middle of a war so we couldn’t predict anything.

Leaving Sarajevo was a horrifying trip and every few kilometres we would have to stop at a new barricade, the bus driver would show them documents or pay them. We were shot at and it was scary. Close to the Croatian border we were stopped by the military and they wanted a woman to stay with them. I looked out of the window and recognised my uncle, so I walked up to my uncle and said I want to go with you.

These camps were not registered, and they often just shut people in abandoned warehouses so there were no official records that they even existed. People were just taken there, their destinies unknown – there were rumours of tortures and worse…

He didn’t recognise me, but he took me to his house anyway. The Croatian military started coming to my uncle’s house, saying that they needed to take me to a refugee camp, but in reality, it was more of a prison/concentration camp. These camps were not registered, and they often just shut people in abandoned warehouses so there were no official records that they even existed. People were just taken there, their destinies unknown – there were rumours of tortures and worse, and I knew that unless I left my uncle’s house that would be my fate. I had heard about the camps and I knew I had to escape so I locked my cousin (who was left there to look out and watch me) in a bathroom, took my stuff and left. I did have an aunt in Split, but she was married to an extreme nationalist, so staying with her was not an option.

When I finally got to north Croatia, to city called Rijeka, I applied for refugee status as a minor and got it. I went to my second uncle’s house, but there was a constant mass of people asking me why I was there, the atmosphere was quite toxic; refugees in the area were robbed and abused. I couldn’t stay there long, so I went to social services and they put me in student housing. It was different there because of the children – they were my age, and there were other refugees.

For nearly two years I dressed as a boy, it was my defence mechanism because physical violence was rife in Croatia in the 90s and it helped protect me from sexual abuse. I had to hide my refugee identity and I made sure never to confront anyone.

The atmosphere in Croatia was very problematic, there were distinctions made between refugees. Those marked as full-blooded were given far more rights than those of us who were mixed, we weren’t given the same access to housing, food, legal help or education. There were some humanitarian organisations handing out milk, oil and potatoes etc but it very infrequently, like every 45 days or so because they didn’t consider that area a dangerous zone for refugees, and because I had social housing I didn’t count as someone who needed additional help. Very often we had to choose between food and housing, and I would always choose the safety of an indoor place. I don’t even want to think about what would happen to me if I would sleep on the street – even for one night. For nearly two years I dressed as a boy, it was my defence mechanism because physical violence was rife in Croatia in the 90s and it helped protect me from sexual abuse. I had to hide my refugee identity and I made sure never to confront anyone.There isn’t a lot of information about how people were treated in Croatia because they were not part of the EU then, a little bit was exposed during the war but there’s no interest in doing research about it now.

As soon as I got to Croatia, I enrolled myself in school, but after 6 months they told me I needed Croatian citizenship to continue. My aunt from Sarajevo came and I have stayed in her house (in the southern part of Croatia) during winter holidays. She helped me get the citizenship so I could return to high school right after the holydays were over.But many of the refugees who were with me couldn’t get it and couldn’t continue with their education. Many refugees had to go back to Bosnia and then they disappeared. I remember when I submitted my high school thesis that one of the professors left in protest because she didn’t believe I have a right to claim even a high school diploma; she thought I was not Croatian. It was very difficult getting a diploma and fighting for my basic rights. I only got through school and into university because I got the citizenship. It was a different sort of horror. You’re in a city that used to be part of your country (Yugoslavia), you speak the same language but at the end you’re being separated and moved around as someone who can’t participate in society.

Families were destroyed in the war. My family and society were divided, no one was helping each other. Sarajevo wasn’t the same place I left as a child; I lost the entire country I was born in.

I was horribly lonely growing up. I wanted to go back home because it was terrible without my family and people shouldn’t be separated from their kids. It’s a huge trauma and I would go back to pre-war Sarajevo, but it wasn’t the same city. At some point my parents couldn’t see me as their daughter any more, I didn’t really exist as family for them. The war, hardships, everything alienated me from them, I was not present and I believe that, at some point, they thought I was dead. Families were destroyed in the war. My family and society were divided, no one was helping each other. Sarajevo wasn’t the same place I left as a child; I lost the entire country I was born in.

I remember once, I went to see my house and the zoo beside it, but it was completely destroyed. The hospital beside it had been turned into a military base for UN personnel. We used to have trees and boulevards, but they were cut down. I remember standing there in shock, looking at my house as the Italian army shouted profanities at me from across the street, asking me to sleep with them. The people, community, self, identity and country were all destroyed. Sarajevo was a magical, beautiful city but I can’t reach out to those things and people anymore. Any good memories I had from that time I compare to the reality today and it’s not great. There’s nothing that can motivate me to go back now.

My colleagues and friends didn’t perceive me as a refugee because they couldn’t put my image and refugee together. They thought refugees were terrible, dirty, violent… It’s difficult when people don’t see you for who you are.

When you don’t have anyone else, you’re responsible for yourself. University was the thing I wanted to do because I wanted to be educated and I wanted to be around tolerant people. I just needed to feel safe somewhere, I had to compose myself and reinvent myself after every blow, incident and shock I went through and tell myself this is who I am and what I wanted to do. I had meetings with myself, I had to decide by myself what I wanted to be. It was like reinventing myself every time. You communicate with other groups and through them you see yourself differently. My colleagues and friends didn’t perceive me as a refugee because they couldn’t put my image and refugee together. They thought refugees were terrible, dirty, violent… It’s difficult when people don’t see you for who you are. They ignored the fact that I was a refugee and decided I was something different because they could relate to me.

I strongly believe I’m Yugoslavian but honestly, I identify as a refugee. When I started working with refugees in Paris, I connected with them even though we don’t have the same language or background. The first document I ever had was a refugee document, my entire adulthood, adult experience started from there. I work with refugees because I perceive them as my people. I don’t have problems with camps or refugees, it’s more difficult to deal with judgemental, racist, elitist and discriminatory people. With refugees I feel safe, I can help, it’s not traumatic because I feel like I’m home.

The word refugee has a certain set of experiences associated to it that isn’t relatable to many. Refugees have a certain set of experiences and tragedies that connect us. For me it’s always a miracle that I survived the war, exile, and now I’m living in Paris. I made something I never thought I could: from being a refugee in Croatia to coming all the way here. Every country has a different standard when it comes to refugees, I think things got worse in Europe because of the Dublin System. The problem is that anyone who makes decisions about refugees doesn’t care about them. You can’t care about them if you don’t engage and meet them to understand their issues and stories.

I would like to write a book or direct a film, because usually everything made about refugees is by someone else and they are represented in offensive ways. Either refugees are criminals or saints. There is no mention of the challenges people go through, things aren’t black and white. I want to tell people the honest truth about refugees.

I hope the perception and treatment of refugees’ changes because it is awful. It hasn’t changed much since I was a refugee. The biggest difference now is social media because of the testimonies given by refugees and volunteers – this is changing things. I would like to write a book or direct a film, because usually everything made about refugees is by someone else and they are represented in offensive ways. Either refugees are criminals or saints. There is no mention of the challenges people go through, things aren’t black and white. I want to tell people the honest truth about refugees. Refugee numbers are growing, and this amount of people might change something, and the presence of social media could give us a window to provide a clear picture of who a refugee actually is.