Hello my name is: The Refugee List

We sat down with Christoph Jones, the creator of The Refugee List to find out more about what motivated him to start the project and how he feels about the current rhetoric used to describe refugees and asylum seekers.

What inspired you to start the Refugee List?

It’s hard to use the word ‘inspired’ when discussing the conception of an art project intended to commemorate individuals who perished as a result of intentional political decisions. Perhaps the word ‘motivate’ would be more accurate.

I was motivated by my frustration at the reporting that surrounded refugees. The 2015 refugee ‘crisis’ was a daily talking point in the media, with the majority of the mainstream reporting presenting refugees as a “swarm”, intent on ”invading” and taking over “British culture”. The echoing of Nazi rhetoric felt entirely intentional and the concept of “British culture” was undoubtedly a dog whistle to white supremacy. The whole bloodthirsty and overtly racist charade continued for many months.

In June 2015, 3-year-old Alan Kurdi and his family fled their home in Syria, for the second time, to escape the brutal civil war and potential slaughter at the hands of ISIS rebels. Three months later a macabre photograph of his cold lifeless body on a Turkish beach, was on the front page of almost every newspaper in Europe. The same journalists and media organisations that for months prior had made their living by demonising desperate refugees, were now shedding crocodile tears and declaring the whole situation a “human catastrophe.”

It could be said of this super-sonic reversal of messaging that the newspapers, and the complicit journalists, suddenly realised that with the appearance of this photo their whole crypto-fascist grift had been shown for what it was and public opinion had turned against them. However, I think that in reality they simply know that a photo of the corpse of a non-white child will sell well in Europe. This is just another example of the struggle of minorities being co-opted into trauma-porn for bourgeois Europeans.

I was sickened by the way the media, politicians and the European public can be so shocked by this singular, unarguably traumatic and unnecessary death, and yet be so ignorant that thousands of children like Alan Kurdi have perished needlessly because of the same policies. It became clear that the media only (pretend to) care about – and therefore the people only become aware of – the thousands of innocent people ending their lives on the borders of Europe when there is a macabre aesthetic to accompany the ‘story’.

During conversations I had with dozens of different people on the topic of refugees and refugee death, people were always shocked to discover that the fate of Alan Kurdi, and the 39 Vietnamese refugees who were found in Essex frozen to death in the back of a lorry in 2019, were not rare and isolated incidents, but instead stand-out events as part of a continual slaughter.

I decided I wanted to attempt to fill the blind spots of privileged and (unknowingly) ignorant Europeans (myself included) with the reality of the policies that they’ve been told exist to keep them safe.

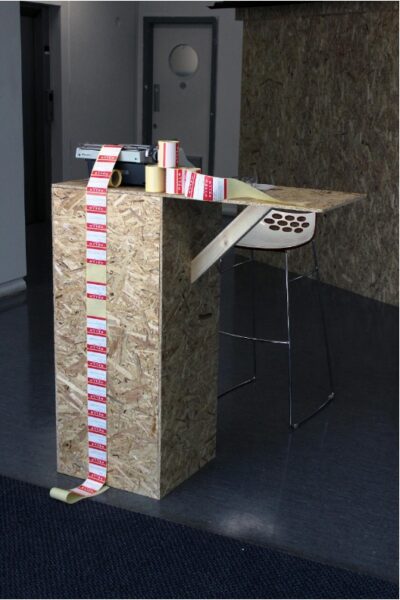

In 2019, the final show of my art degree was scheduled to happen. It was an event which provided a rare platform that would garner a lot of attention. I decided to take the opportunity to highlight the reality of life for refugees as much as I could. The exhibition consisted of a refugee shelter recreated according to UNHCR guidelines in the gallery space, mirrors etched with the testimony of a Syrian refugee forcing the reader to literally look themself in the face as they read, a collaborative video piece with the unspeakably brave Syrian refugee Muhammad Najem who was only 16 at the time, and the piece that came to be known as ‘The Refugee List’.

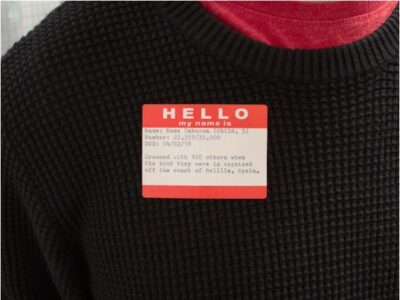

At the time the piece existed as a kind of performance. I stood at a small desk with the List of Refugee Deaths, compiled by United For Intercultural Action, and a cold-war-era typewriter, meant to reference the fall of the Berlin Wall and the over 1000km of border walls that have been built in Europe since. Throughout the exhibition, I typed the details of the victims into name stickers, one sticker for each person who perished. As visitors entered the gallery I would walk up to them and say “Hi, I just need to give you your name label.” Before they were able to work out how I could possibly know their name, I’d affixed them with the identity of a victim. At the conclusion of the exhibition, I had branded over 600 people with new identities.

The reaction from what was, on the whole, a middle-class, white audience was more palpable than I had anticipated. Groups would be reading each other’s labels and having conversations about them. Individuals came up to me and said they feel like they can’t take the label off. Others said they felt a personal connection to the victim, as if they’d been charged with their remembrance.

Following on from the exhibition I thought a lot about my role and responsibilities concerning the artwork and the victims. I felt that to simply roll out the piece at the occasional exhibition would be tantamount to appropriating the deaths of refugees for the benefit of my art career. My goal with the artwork was to commemorate the victims and raise awareness in the public sphere. I decided that I needed to complete the list.

I created The Refugee List Twitter account in June 2019. The intent was to have a place, accessible to everyone, that can host the regularly posted ‘labels’, starting with the earliest documented case on the list, (an 18-year-old woman who died in a racist arson attack on a refugee camp in Germany) working chronologically to contemporary tragedies. The images are made with Adobe Photoshop and were originally posted manually, meaning that I could only commit to posting a handful each day. I realised that with an average of 6 refugees drowning every day in the Mediterranean Sea alone, it would take me over a decade to catch up. From that point, I invested in using auto-posting services which have allowed me to schedule posts to be published automatically each hour. Although this saves me hundreds of hours of work, The Refugee List has and will always be a labour-intensive project.

The nature of Twitter allows for an element of virality, and The Refugee Lists posts receive hundreds of likes and shares each day. This aspect allows the memorials of the victims to reach a much wider audience than could ever be achieved in the offline realm. With the help and support of many wonderful organisations and individuals, I regularly see that people whose only exposure to the plight of refugees is through the media, come to the quick realisation that they’ve not been told the whole story and that in fact, the story might have been a falsehood entirely. The combination of memorialising the tens-of-thousands of mostly unnamed victims of the anti-refugee political policies often collectively referred to as ‘Fortress Europe’, combined with the enlightening and radicalising nature of discovering these memorials ‘in the wild’, makes any financial or labour sacrifice on my part more than worth it.

What do you think of the rhetoric used by politicians and the media regarding refugees and asylum seekers?

The rhetoric of European politicians is unquestionably intended to be harmful. It’s not an accident that language of racism and demonisation is the only language used in reference to refugees and asylum seekers, barring a handful of more left-wing political groups. However, I truly believe that it is entirely artificial. Other than the most overtly hateful far-right cultists, there are very few politicians who honestly believe that refugees are a real sociological and economic problem for their country. Study after study has shown that rather than a burden, refugees are overwhelmingly a massive cultural, economic and social boon for their host countries. I would like to highlight that I personally believe that human beings have an inherent value and right to life, beyond their economic contribution, but the cold neoliberal heart of European politics often corrals us into economic justifications for the safeguarding of the innocent and vulnerable.

I am certain that the leaders of Europe are very aware that refugees, or “migrants,” or “illegal immigrants” – whatever thinly-veiled slur they choose to use – should be a welcome contribution to their country, but increasingly politicians around the world have shown that the politics of late-capitalism is not one of representation and truth, but the attainment of power exclusively. When politicians know that they can excuse, cover-up, obfuscate or justify almost any political decision through the demonisation and othering of refugees they won’t hesitate to do so, facts be damned.

Donald Trump’s infamous 2016 presidential campaign speech, during which he labelled Mexican refugees as “Drug dealers, criminals and rapists”, racist stereotypes manufactured for decades by successive Republican and Democrat politicians, perfectly exemplifies how presenting the vulnerable as a dangerous, wild hoard intent on taking over your safe (i.e white) country, can scare the populace into voting them into power. Touching on the ignorance of Europeans, and their arrogant attitude that Europe is some sort of progressive, welcoming continent, during the 2016 presidential election I witnessed the reaction of many Europeans deriding the Americans as being backwards racists, with the smugness of a civilisation that is ignorant to identical terrors occurring at its own borders. This ignorance is a tool of hegemony in Europe. It allows the plight of refugees to be a tool wielded to control the populace through fear. If Europeans were acutely aware of the true causes of forced migration, who is often responsible for this and what should actually be done to improve the situation, then the leaders of Europe would not be able to so easily scare the people into providing them power.

The leaders of Europe invent a false enemy in the form of people who are unable to stand up for themselves in European society and then tell the people of Europe “Vote for me, and I’ll protect you from them!” Once again, the mirroring of Nazi rhetoric is, in my opinion, not entirely unintentional.

There are many incredible journalists whose work is invaluable in discovering and sharing the truth of the situation. These individuals work extremely hard to uncover and report on the lives of refugees and the political machinations that lead to people becoming refugees. The Refugee List and the work of many incredible activist organisations would not be possible without the tireless investigations and reporting by these principled individuals. Sadly, however, they are rarely in mainstream positions meaning their work and the truths they expose are fighting against, and obfuscated by, mainstream political and media spin.

When it comes to the mainstream media, I am increasingly of the opinion that they are exclusively made up of privileged, private-school toffs who care little for anything beyond their own success and the maintaining of the exclusive status-quo that they benefit from. They are nodding dogs, doing the bidding of their billionaire paymasters, invertebrates who will joyously condemn the innocent and vulnerable to unspeakable terrors, and then write opinion pieces about why ocean pushbacks are actually a good idea, a practice that violates international law.

During the increase of refugees attempting to cross from Calais to the UK in 2020, the BBC reporter Simon Jones caused outrage by pulling up alongside a small dingy of young refugees in the Channel and filming them bailing out their tiny vessel, which was filling up with water. Jones said “We have seen them trying to get water out of the boat, they’re doing that at the moment, they are using a plastic container to try to bail out the boat. Obviously, it’s pretty overloaded there. People are wearing life jackets, it is pretty dangerous, just the number of people on board that boat.” Clearly, Jones understood that the people were potentially in serious danger, however, neither the reporter nor any of the other crew attempted to rescue them, acting as though they are instead required to leave the victims to their fate, like some depraved wildlife documentary. The ’report’ was quite simply an act of sick voyeurism and the monetisation of a manufactured circus of terror and death on behalf of the powerful and their thinly-veiled white supremacy.

After receiving over 8000 complaints about the report, Jones, presumably realising that showing the reality of refugees works against his intended aim, retreated to his official Twitter account where, to this day, he instead reports the number of “migrants” that have landed on Britain’s shores. Jones is a cowardly propagandistic bottom-feeder who gladly whips up fascist rhetoric against the vulnerable to keep his paymasters in power and, most importantly, himself in a job. Jones may be a staggeringly unprincipled and an ignorant stooge, but he is an unremarkable and insignificant person in the grand scheme of things, just one example of the stream of racist and craven reportage that is integral to maintaining all of Europe’s murderous policies.

Why do you feel art is important to draw attention to refugee/humanitarian issues?

Ultimately, art is a tool of exploration and communication, be it political, spiritual, aesthetic, philosophical or whatever. Whether the expression of some deeply personal and introspective feelings on behalf of the artist as an individual or a communal work of collective or national celebration, the unspoken goal is to communicate these ideas/feelings/visuals to others. The aspect of art that makes it effective in this regard is that the limitless and subjective nature of the practice allows for incredibly immersive, captivating and memorable ways of communicating. Art is experienced, rather than just seen, read, or heard. (Of course, this doesn’t discount the communicative ability of written text, music or film. In fact, one of the best artworks concerning refugees, in my opinion, is the heartbreaking and powerful poem Home by Warsan Shire that I urge you to read.)

I think this tactic makes it possible to convey ideas that may be complex or take a lot of explaining in a simple and impactful way, that can use the commonly held experiences and knowledge of the viewer to rapidly instil an understanding. Of course, almost anything can be explained via text or film etc, but why would someone want to read a long-winded text (such as this one!) about the suffering of tens-of-thousands of refugees, when a simple sticker could engender the same or better emotional connection in a fraction of a second?

Art, however, has its limitations. I think those that treat art as some sacred arbiter of inherent truth and value are as misguided as those that declare that art has no activistic capabilities whatsoever. As I said, art is a mechanism for communication and can be bad at communicating for a plethora of reasons. Art that communicates badly is bad art by my judgement. There is also the fact that art can be tainted by the ignorances and prejudices of its manufacturers and originating society. These blemishes should be taken into consideration with extra sensitivity when manufacturing activistic art, it’s easy to get overcome by righteous anger and forget the mindset in which the average viewer will interact with the work – ranting might feel cathartic, but it’s off putting and patronising to those not part of the in-group (I’m constantly guilty of this artistic faux pas). It’s also important to ensure that the work is well researched and honest. Any inaccuracies will only damage the message of the work and therefore the ability to convince the viewer. It could even undermine the movement as a whole. The art studio floor is littered with ineffective and unconvincing artworks, many of them my own.

How do you feel about the work you’re doing and about the need for the Refugee List to exist?

I think the work serves a necessary purpose of both symbolically commemorating the victims of ‘Fortress Europe’, and also making people aware of the staggering numbers of people that are unnecessarily killed by these policies. There is an aphorism (often dubiously attributed to Joseph Stalin) that goes something along the lines of “One death is a tragedy, a million deaths is a statistic”. Statistics are inherently cold and uncaring, they obfuscate humanity. The statistic that at the time of writing, over 45,000 innocent people have died as a direct result of ‘Fortress Europe’, doesn’t show you these people‘s names, it doesn’t show you the unimaginable suffering that is an intentional characteristic of this type of death. The Refugee List is about breaking through the heartlessness of statistics.

Alas, The Refugee List has severe limitations in this regard. It can’t show you the victim’s face. It can’t show you their dreams. It can’t show you their favourite music. It can’t show you their first kiss. It can’t show you their new car. It can’t show you their favourite country walk. It can’t show you where they hid from the bombs. It can’t show you what they saw that convinced them to leave. It can’t show you the things they had in their pocket as they ran away from home. It can’t show you the horrors so severe it made them take their chances with ‘Fortress Europe’. It can’t show you the bullets they ducked from and illegal minefields they crossed. It can’t show you the heart-wrenching realisation that they were about to die, thousands of miles from home and so close to salvation. It can’t show you the tears on the cheeks of their loved ones knowing that the days and weeks without a word tell them that their child has perished – but they will never know for sure. It can’t show you the symbolic grave, made for a person whose body will never be found. It can’t show you the stroke of a politician’s pen that knowingly condemned them.

The Refugee List can give a fractional glimpse at the conclusion of a life, but it can’t reveal the full spectrum of that life or its potential future. This was ensured by the politicians, media, coast guards, border guards, fence builders and trench-diggers of Europe, each one culpable.

What challenges have you faced when compiling and disseminating this information?

I feel a bit uncomfortable talking about my personal challenges and difficulties relating to this project as, no matter how hard the struggle is, it’s nothing compared to any of the individuals on the list. The one thing I will say, as I think it highlights the horror that these refugees have to deal with as a characteristic of their existence, is that for a long time the exposure to the project took a toll on my mental health. As part of reformatting the original list, a process that took several months of manually re-typing each entry, I read every single entry on the list, a 700,000-word book of slaughter. I read an entry for a man, then an entry for a woman, then an entry for two young children. All of them had died in the same place and at the same time. Clearly, in the coldness of the statistical reportage, is the documenting of the final moments of a young family.

The stress I feel from reading these entries, and tens of thousands more, is infinitesimal when compared to the horror these people were forced to endure at the end of their lives. Nevertheless, confronting horror on such a consistent and prolonged basis was profoundly unpleasant, even if it was my choice. I’m sure this is a feeling that many activists also have to deal with.

Who is your primary audience and what message do you hope people take away from your project?

My primary audience is people who wouldn’t usually be exposed to the reality of the scale of slaughter at Europe’s borders. Activism can often preach to the choir, I wanted to avoid doing that as much as possible.

There is obviously a contingent of people who have fully drunk the Kool-Aid of far-right, propaganda put out by the UK’s Home Office and right-wing governments and media organisations around Europe. These people have allowed themselves to be so scared by the anti-refugee propaganda that they see instances of refugee suffering as some kind of success. Or at least that’s what they say in the comments of the project on Twitter. (I suspect this is merely over-compensation for them being forced to face the reality of their ideology.)

These people I don’t worry about, it takes more than a Twitter post to de-radicalise someone that far down the right-wing pipeline. I’m looking for my work to appear, unannounced and uncalled for, on the timeline of someone who can have their mind changed or just come to understand the truth and be motivated by this change in perspective. I suppose I’m aiming for people who come from a background that is unlikely to contain a history of migration. Probably white, probably born in their country of residence, probably liberal or a centre-right conservative, probably middle-class.This broad demographic tends to, on the whole, not be overly hostile to refugees, beyond the standard resonance of anti-refugee scepticism.

These are people whose only direct exposure to refugee suffering is the occasional sensational instance of death as discussed above. They understand that it’s a “tragedy”, but they’re not aware of how sustained and manufactured the tragedy is. Obviously the nature of the project means that it doesn’t discriminate or target any specific demographic or individual, and the efficacy of the interaction is hard to know. But if it changes some minds, enough to encourage progress, then it’s been successful.

What barriers exist for your audience to know about refugees and the current hostile environment they are facing?

I think the biggest barrier is the relentless propaganda pumped out by the governments and media of Europe. As mentioned above, the vast, vast majority of people find the struggle of refugees to be a tragic and unacceptable occurrence, once they are made aware of it. People cannot fight for the rights of refugees and for the implementation of hospitable political policies if they have no truthful understanding of the situation. Again, if people’s only real information on refugees comes from sources who present them as invading hordes, sprinkled with the occasional “unavoidable tragedy”, then there is no chance for the overwhelming power of the people to put weight into saving refugees, rather than condemning them.

Doing the work, you’re doing in 2022, how does that make you feel about the state of humanity?

I feel good and bad, I think of myself as a pessimistic optimist. It is hard not to fall into the void of nihilism and complacency. The status quo is a strong beast, being fed and maintained by the most powerful and wealthy people to have ever existed. David defeated Goliath, but Goliath wasn’t in control of every aspect of David’s life, the economy, the law, and the military. David didn’t rely on the giant for job security. The world is a frustrating and lonely place at times, especially if you care about it.

That said, I believe, with every fibre of my being, that an infinitely better world is not only possible but inevitable. Frankly, if it were not for the forces of capitalism (who have a vested interest in the status quo and divide-and-conquer tactics), acting as a dam, then the tide of progress would already be washing through the valley of time. Contrary to the abhorrent conspiracy projected by capital that individualism and selfishness is some inherent human trait, the fact is that community is the evolutionary core of humanity. Only the powerful have an interest in placing borders between communities and defining one side as “Us” and the opposite side as “Other” – because when you’re busy fighting against your equal, you’re not fighting against your oppressor.

I think that every day the inability of capitalism and its craven adherents to care for the vast majority of people is being made clearer and clearer, even more so since the beginning of the Covid pandemic. I am optimistic that sooner rather than later, we will have a unified, global realisation that a system of collectivism rather than individualism is necessary for the survival and progress of humanity, let alone the emancipation of refugees.

Why is it vital to have an organisation like the Refugee List and what do you feel differentiates your project from others?

It’s hard for me to declare that The Refugee List is “vital”, maybe simply “important”. I think the project is one small cog in a machine that’s pushing against oppression. If you remove the cog the machine will probably not stop working altogether, but it would be less efficient and less powerful.

I think the characteristic that makes The Refugee List unique and engaging is the unpredictability of each encounter with the project. Whether it’s in the art gallery, on the street or on Twitter, the work and the message is forced upon the unprepared viewer. This instantaneousness, combined with the brief but harrowing narrative of an individual’s final moments, generates an honest reaction in the mind of the viewer. Their experience is free from ideology and propaganda, pure and real, their honest feelings and natural empathy take over.

The hope is that this empathy remains the next time they see a headline talking of “hordes of illegals” and “economic migrants”. At that point, they’ll realise that they’ve been lied to, and the next step is to ask what truth is being obscured by the lie.

From that point progress is inevitable.

Christoph Jones is a British conceptual artist currently studying at the Royal College of Art in London.

The Refugee List

Instagram: @refugee_list

Twitter: @refugee_list

Christoph Jones

Instagram: @_christophjones

Twitter: @_christophjones