It’s very sad to see history repeating itself, we never learn any lessons

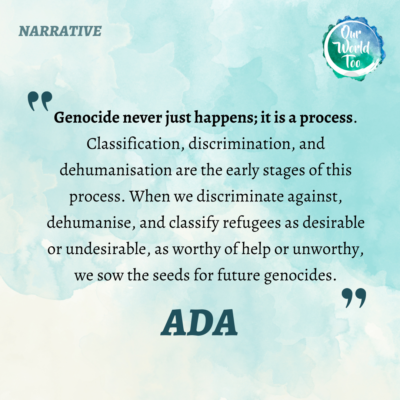

Genocide never just happens; it is a process. Classification, discrimination, and dehumanisation are the early stages of this process. When we discriminate against, dehumanise, and classify refugees as desirable or undesirable, as worthy of help or unworthy, we sow the seeds for future genocides

Before the war, my family and I lived in the suburbs of Sarajevo. I was around 3 or 4 years old, and my brother was 2 years younger than me. My mom was a doctor and my dad worked in the government. We had an ordinary middle-class life, and we were happy. We spent the weekends with my grandparents in the city centre and we had a weekend house in the countryside where we used to play with the local children.

We started hearing about the possibility of war on the news. The tensions in the Balkans were high as Yugoslavia came apart. We heard about Slovenia declaring its independence and the one-week war which followed. Then news started spreading that Croatia and Bosnia also wanted to vote for independence. Serb nationalists started spreading propaganda saying Bosnian Muslims wanted to make Yugoslavia a Muslim Kalifate.

My parents remained optimistic despite the news, they were convinced it wouldn’t get worse, that it would be just like Slovenia. They ignored the news for the most part but day by day there were signs that things weren’t going well. There was a visible increase in military presence which was marked by military aggression and civil unrest. Gradually, there were fewer and fewer things available in supermarkets because the supply chain was disrupted when the war was announced.

Because I was so young, I didn’t totally understand what was happening. My memories are fragmented. I remember the soldiers, tanks, and gunfire. I remember being afraid because the sounds were so loud and frightening. We were young and the adults were trying to protect us. It was almost like I was a passive observer because I wasn’t fully aware of what was going on.

We lived in flats and there were a lot of fields around us for us to play in. I remember waking up one day and looking outside and I noted tanks rolling up. Snipers also stationed themselves in the block of flats opposite ours. It was impossible not to notice the increasing military presence.

Then the shelling and sniper fire began.

It didn’t take long for my parents to realise we were no longer safe in our neighbourhood because the Serbs were closing in. They used to tell us to not go too close to the windows because they’d heard stories of people being hit by stray bullets. Eventually, we moved in with my grandparents because they lived in the centre of Sarajevo and were further from enemy lines. We stayed there while my parents decided what to do next.

My parents aren’t religious, but we are ethnically Muslim. We would’ve been targets. My parents decided it wasn’t safe for us to be in Bosnia anymore.

Before the collapse of Yugoslavia, the JNA had been our army, but it was now part of the Serb forces. We still had extended family serving in the JNA and my parents spoke to him to see if there was some way we could leave. He pulled some strings and put out names on a list at the airport, he told us we could leave as refugees.

At the time, there was a petrol shortage, and we didn’t know if we had enough petrol in the tank to get us to the airport, but we set off anyway. We thought of taking a taxi, but it was too dangerous. We drove to the airport, down sniper alley and past checkpoints. At the airport, my mother, brother, and I were allowed through, but my dad was turned away. Like in Ukraine, the Serbs refused to let men of fighting age leave the country.

My aunt had married an Englishman and we had family in the UK who could vouch for us. We came to the UK in 1992 and stayed with them. My dad was in Sarajevo during the siege, and we didn’t know if he was alive or not. The letters he sent took months to reach us. Eventually, he managed to convince a journalist to help him get to Croatia. He went to the UK consulate in Croatia and claimed asylum.

During the war, I remember a conversation I had with my dad, I told him he’d taken me to my grandpa’s house and grandpa had given him a gun. He was surprised I remembered it, but that confirmed it had happened. I have these vivid memories, but it feels like they were in a film. Like they weren’t happening to me. I was confused and sad about my dad not being with us.

I was put into primary school right away. I didn’t speak English and I couldn’t understand it. I used to get into trouble a lot because I didn’t understand the language or the system. I was frustrated because I couldn’t express myself verbally and got angry with the other kids. In the beginning, I found it hard to socialise. My mom kept my report from primary school, and it said I didn’t smile or laugh. It was a language and culture shock; I was just thrown into school. I was coming to terms with being in the UK, with being different, with being the other.

We were in Henley upon Thames and there weren’t many other immigrants. The older kids knew what was happening in Bosnia, everyone knew me and my story. I received a lot of negative attention. I was picked on for being a refugee and I felt lonely and alienated.

When we moved to the UK, my mom made friends with a Balkan refugee artist who would babysit us sometimes. They gave me their old paints and I started painting pictures of my old life and of war. It was a creative outlet for me to process my emotions and memories. It helped me deal with themes throughout my life.

I now work as an illustrator and animator. I often explore my experiences of being a refugee through my art. I did an Art Foundation degree before university and my project focused on my memory before the war and my heritage. Later for my university thesis, I spoke about how Muslims are portrayed in political cartoons. I started to illustrate other people’s experiences and stories. I keep coming back to art to help me make sense of who I am and to help other people do that as well.

Anyone can become a refugee, but the media portray it as some being more deserving than others.

When I think of the term refugee, to me. It means my family’s story and their sacrifice. It means the obstacles they faced and the opportunities my parents gave us by leaving. For refugees around the world, there are obstacles, whether it’s the colour of their skin or their reason for being a refugee. Whether the experience is difficult or easy comes down to the perception of who you are and where you’re from.

Anyone can become a refugee, but the media portray it as some being more deserving than others. When my mom and I see the opinions being shared and the political take on Ukraine, they don’t remember or mention Bosnia even though it was also on European soil. They just say it’s terrible because it’s happening in Europe and happening to white people. It’s very sad to see history repeating itself, we never learn any lessons.

If we stop and look at the statistics of which countries take in the most refugees, it’s clear to see it isn’t an issue in the UK. We are not being overrun.

I feel it’s worse for refugees today. The attitudes toward refugees have gotten worse and the way the media maligns refugees is poisonous and unpleasant. I don’t believe anything they say, but I think other people do. They believe the refugee situation is out of control. If we stop and look at the statistics of which countries take in the most refugees, it’s clear to see it isn’t an issue in the UK. We are not being overrun.

The media demonises refugees and they say we’re being swamped. They’ve created a poisonous climate where refugees are demonised and hated. None of it is based on facts but because of the media narrative, no one believes it.