Peace isn’t the absence of war, it’s the steps we take to stop war

Smajo was only 9 years old when he and his family were forced to flee Bosnia after years of being internally displaced because of the Bosnian Genocide. In conversation with Our World Too, Smajo shares what it was like experiencing the Bosnian Genocide as a child and his opinions on the current rhetoric surrounding refugees.

People have this delusion that we are so very different from the monsters who commit genocide, but they were once normal people too. They went to our schools, they were our friends and neighbours, but they changed. Society turned against us. They dehumanised us but in the process of doing so, they also dehumanised themselves.

The Bosnian Genocide lasted from 1992-1995 and resulted in millions being displaced, thousands being killed and culminated in the worst genocide in Europe since WW2. While it is important to commemorate the number of lives lost, it’s impossible to describe loss through numbers alone. Numbers can’t describe the pain of losing a loved one and they can’t describe the lasting impact war has on a child. We asked Smajo about when he realised things around him were changing and what his first experiences of war were.

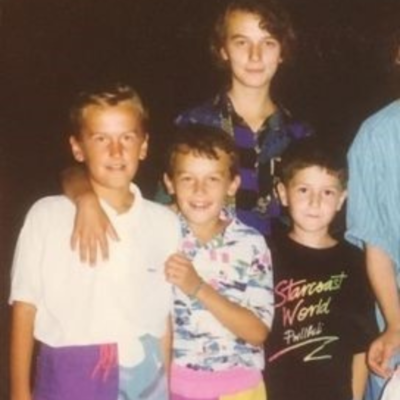

The tensions had started a few years before the war, but I had been too young to notice. I was 6 years old when things around me started changing more obviously. I remember the kids started playing war and it was an obvious indication of what was being discussed at the time. My grandmother used to say it was never a good sign because she remembered the same thing happening before WW2.

I remember my brother had a bike he was extra protective of but suddenly one day my parents allowed me to ride it and even though I was suspicious, I didn’t question it.

I have all these pockets of memories of waking up and overhearing the adults discussing whether the international community would help us. I used to see my mam crying and I didn’t know why she was upset but it made me upset to see her like that. At the time, I had this little German Shepard called Lesi and whenever I used to ask questions about what my parents were discussing my mam would distract me by saying they were talking about someone’s dog that had run away when they were in fact talking about the notorious Serbian war criminal, Vojislav Šešelj. I remember my brother had a bike he was extra protective of but suddenly one day my parents allowed me to ride it and even though I was suspicious, I didn’t question it. As a child, you have to deal with all of this information and piece things together.

In 1992, the Serbs rolled through my hometown and set up camp just outside. In the sunshine, we could see the gleam of their bayonets. My dad and his cousins went to investigate and ended up bringing the commander back to our house. The commander said he wouldn’t hurt us because my grandfather and his brothers saved Serbian towns and villages during WW2 from the Ustase and Nazis. At the time, my uncle lived in France, and even before this we had a chance to leave, but my parents didn’t want to leave because we’d just built a new house and my dad had a job.

Serbs who had once been our neighbours and friends now surrounded our town. They used to come over with tea and now they had guns. In the beginning, Serbs we knew were stationed in my hometown and when they searched our house, they were nice about it because they had sympathy for their Muslim friends. That didn’t last long, and the local Serbs were replaced with non-locals to disrupt local relations. When the non-locals searched our homes, they were rude about it. They didn’t want any resistance, so they searched our houses for weapons – when they were the ones committing atrocities against civilians, women and children.

I remember I was sick one day and my dad took me to hospital. We were able to get there just fine, but on the way back we were stopped by this soldier who was barely taller than my 6-year-old self. He was acting like a bigshot saying he would take us to the prison camp outside Stolac. Luckily, another soldier came up to him and asked him to step aside. The man was an old family friend, he drove us to another friend’s house, and that friend’s son put on the Serb uniform and drove with us, to our home.

Up until that point we’d heard sounds in the distance, like the deep rumble of thunder but when the first shells fell, it was only a few metres away from me, my brother and cousin. We’d had this idea to chase the neighbour’s chickens and waited for everyone to leave before climbing over the stone wall. We threw the chickens over the wall because we wanted to see if they could fly. When a shell falls, it whistles and then stops. The explosion happens after that. We were only a few metres away and it was very loud. The wall was shaking, and the chickens were going crazy. To this day, I’m still proud I was the first one over the wall. We hid under a tractor attachment. We thought it would protect us, that was our understanding of war.

There is a romanticised idea of war but when you taste the fear, it goes away quickly.

The Genocide in Bosnia was not based on a religious war, but religion was used to create divides in society and portray Bosniaks as ‘others’ to justify a nationalist and fascist campaign against Bosniaks. Many Bosniaks were forced out of their homes as the advancing Serb forces burnt villages and detained and killed citizens. Speaking about his experiences as a child, Smajo had to live through displacement and watch as his dad was taken away to a concentration camp.

In the weeks leading up to when we had to flee, we moved between our house and a friend’s house at the edge of the village. We used to shelter in the basement with other families whenever there was shelling. Sometimes it lasted for days at a time. We stayed until the soldiers told the remaining Muslim families to leave. We didn’t have time to prepare so we only took what we could carry. Before the war, I had just been about to start school and my mam had bought me a rucksack and school supplies. Those together with a photo album are what I took with me.

I remember the day we left, we walked along the dry riverbed in small groups towards Stolac in the Bosnian heat of June. Before the war we played and swam in the river, now we were using it to escape. Every sound echoed and there was this overwhelming fear they would be able to hear us. I was frustrated and I felt like I wanted to cry. At one point, I tripped, and a stick went into my eye. I started crying my eyes out, it was my opportunity to release those emotions.

We stayed with my aunt in a village between Stolac and Mostar for 2 or 3 days before moving again to stay with another aunt. There were about 20 of us in the house. While we were there, my dad joined the army in Stolac which was stationed about 30 minutes away. We could hear the fighting in Stolac, and we knew my dad was fighting and that it was dangerous. I remember actively listening to what was being said because I missed my dad. Before that, there were efforts to protect the children and not let them know what was happening but gradually that goes out the window.

Bosniak Muslims and Croats fought side by side against the occupying Serbian army until things started changing again. This time Bosnian Croats, with the help of Croatia started arresting Bosniak Muslims. One of them was my dad.

Everyone saw the trucks driving into town and we were trying to figure out what was happening. My older sister saw my dad on one of the trucks, she was just a kid, so she waved at first, but she realised something was wrong and ran to tell my mam. As the trucks were rolling through town, soldiers were searching the neighbourhood for men. My mam tried talking to one of the soldiers she recognised, but he ignored her. When she tried again the second man just told her the men were being rounded up. My uncle was still at home because he had an injured back, but they came back the next day to take him away. My sister yelled at them, ‘you took my dad, you can’t take my uncle!’

After my dad was taken, my mam would stay up most nights standing beside the window. She knew something would happen. A month after my dad and uncle were taken, everyone was thrown out of their homes. The Croatian soldiers came with swords and threatened to rape, cut off our heads and kill us if the Muslims didn’t leave. The soldiers came at the break of dawn, my mam had been anticipating it and already had our bags packed. Until then, we still had Lesi with us. He was our alarm system. He would start barking when something bad would happen, like before the shelling. A few days before we left, he started burying his food and crying. That was the last time we saw him.

We were marched to the factory where my dad used to work, and I remember my hand hurting because of how tight my mam was holding it. She didn’t want to lose us in the crowd. I was on her left, my sister in front and my brother was on her other side. When we got to the factory, we were searched. We started screaming and crying when one of the soldiers grabbed my mam. Seeing my sister cry was like a signal to the soldiers, they rationalised it must have meant we were hiding something.

My sister was wearing a pair of earrings my grandfather had given her when she was born, it was the only connection she had to him. When the soldiers asked for them, my mam tried to reason with them, but they didn’t care. One of them was wearing aviator sunglasses and I could see myself reflected in them. I could see myself crying my eyes out. He tried to bribe me with chocolate to tell him where we were hiding our valuables.

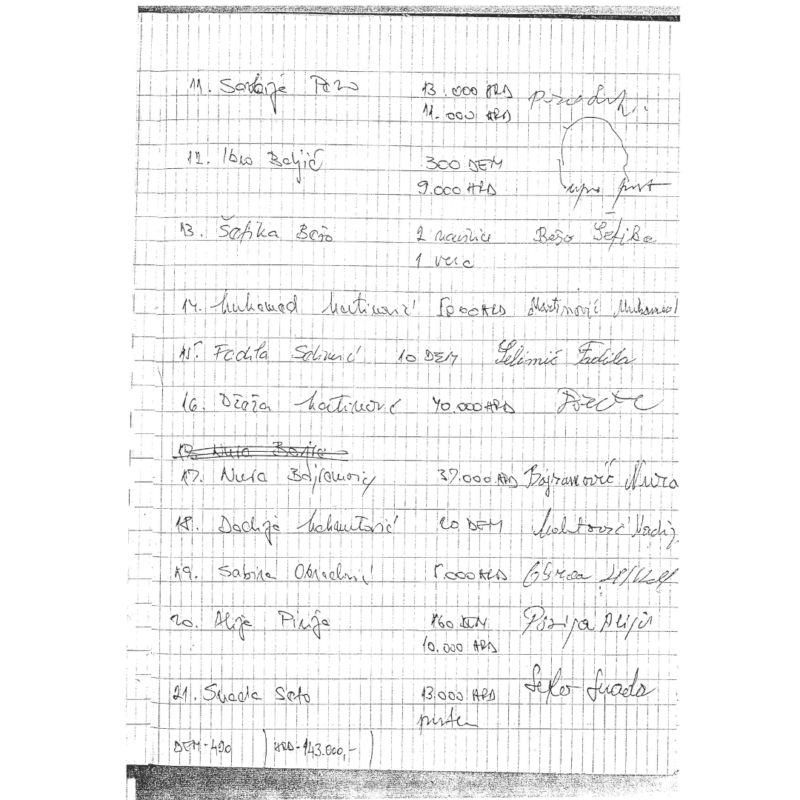

My mam was made to sign a document stating we’d given over ‘two earrings and one ring’ for safekeeping. They took more but that’s what was officially recorded. Obviously, we never saw any of the items again. We had more on us, but my mam had the foresight to sow them into our clothes. Through all of this, my brother had silently sat in a chair, I think the soldiers thought he was with my aunt who was being searched beside us. The other soldier knew my dad, so he only pretended to search my aunt.

He looked at everything we were carrying and shouted at us saying it looked like we had just come back from a vacation in Turkey. It was a reference to 1389 Battle of Kosovo between the Ottoman Empire and the Serbian Army.

When we were sent outside, there was a man waiting there. His shirt was wide open, and he was wearing a giant cross. It only further emphasised the fact that we were different, but we knew this wasn’t Christianity. We knew he didn’t have anything to do with what it meant to be a real Christian. He looked at everything we were carrying and shouted at us saying it looked like we had just come back from a vacation in Turkey. It was a reference to 1389 Battle of Kosovo between the Ottoman Empire and the Serbian Army. They used to call us Turks, like we were foreigners or invaders, but we aren’t Turks, we are Bosnian.

We couldn’t take more than one bag, so we had to wear all our clothes. We were loaded into the back of trucks and it was sweltering. They had black covers draped on top and it was very claustrophobic. Only when the trucks started to move, and someone cut a hole in the side were we able to get fresh air.

We were dropped off outside Blagaj, a town just south of Mostar. We knew where we were but not what would happen, so we just started walking. I saw a chessboard lying on the side of the road. My dad and I used to play chess, so when I saw it, I couldn’t help but tell my mam that we had forgotten ours. At one point I stepped on a foam mattress lying in the middle of the road and the body of an old man was underneath it. That was the first time I saw a dead body. We walked for around 2 hours before we got to Blagaj. We saw our soldiers, but they didn’t let us stop because the area was full.

There is no respite in war. While families wait for news of their loved ones, they also have to establish a sense of normality and routine despite the bombings and fear. In Bosnia, an international arms embargo disarmed Bosniaks and left them vulnerable and unable to defend themselves from Serb and Croat nationalists. Cities like Sarajevo and Mostar were under siege with very little food, goods or medicines allowed in. Despite being under attack, Smajo recalls how his family navigated living under siege.

On 23rd September 1993, the hidden Croat concentration camps were discovered by the Red Cross. 500 prisoners in the worst condition were selected to leave. My dad and uncle were in the same camp, neither of them knew what would happen if they left so they decided my dad would leave and my uncle would stay. My dad was sent to an island in Croatia and my uncle was freed a year later. We didn’t know this at the time because we didn’t have any way to contact them. The last time we had heard about my dad was from a Croatian friend in Stolac right after he was taken, but it had been months since then. When we heard about the 500 prisoners being exchanged, we didn’t know my dad was one of them. The Red Cross used to deliver letters to family members in other parts of Bosnia, but the Croatians used to check the mail and destroy anything sensitive.

Whether you choose to think about it or not, war preoccupies your life. There was an international weapons embargo placed on Bosniaks so we couldn’t defend ourselves. Mostar was surrounded by the Serbs and Croats; they wouldn’t let anything in which included food and medicine. On one occasion alone, our house was hit by 6 shells. The Croats controlled the hill in Mostar and whoever controlled the hill controlled the city. We were completely exposed. The siege of Mostar is usually forgotten but we were surrounded by literal fascists with iconographies from WW2 and Nazi symbols.

By then we had become very skinny, and we used to go to bed starving every night because food was so scarce and expensive. My uncle used to drive a water tanker around Mostar and one day he brought back a loaf of bread. My aunt’s son was awake and was given a slice, but the adults felt bad for the rest of us, so they woke us up in the middle of the night asking if we wanted to eat. We were so happy to eat that dried bread, the adults cried as they watched us. Before then, we’d been eating bread made out of chicken feed, we also used to make it out of this white powder, but we stopped using that when our skin started to peel. My mam used to watch adverts showing starving children in Africa, but now we were them.

The men were mostly fighting so women had to keep communities and our society going, educate children and teach them how to be good human beings. My mam and aunt gave us consistent reminders of what we wanted to be. They reminded us of our beliefs and helped us imagine a world where there is no war, where we were happy, where there was no hatred and where our education wouldn’t be disrupted. It was our way of resisting.

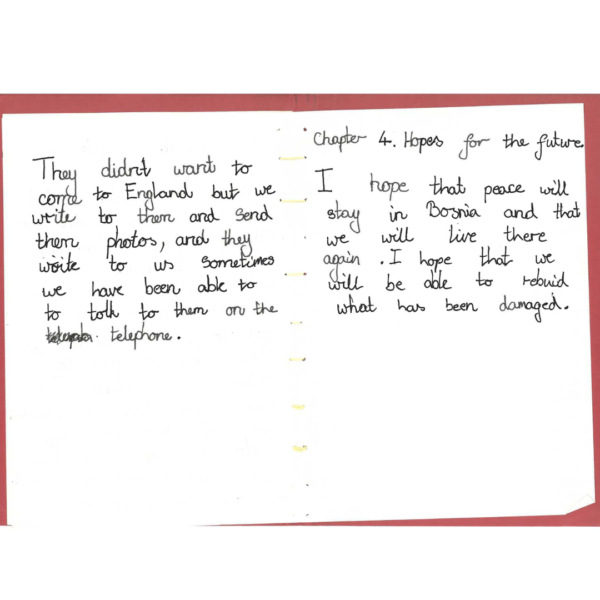

The Serbs and Croats burned books, archives and mosques; it was total cultural destruction. In Stolac, all the museums and mosques were destroyed. Even their foundations were destroyed to erase any traces that Muslims had been there. Over 60,000 women were raped during the war, and we were on the brink of extinction, but we didn’t destroy synagogues, churches, archives, libraries or carry out ethnic cleansing because our religion teaches us not to. Muslims in Bosnia in the 1990s defeated fascism and that’s a fact. My mam and aunt didn’t want us to become hateful. They used to tell us not all Croats or Christians are the same. We still wanted to read and write and send letters to my dad. Despite everything, we were still able to dream.

We had started going to night school, we knew the war would end eventually, and we wanted some sort of normality. On the 23rd of June 1994, a modified crop plane loaded with homemade IEDs flew above Mostar and by then we’d heard so many different shots and explosions we were usually able to tell the different ammunition apart, but we had never heard anything like that. I remember running out of the basement where the school was and up the hill. My aunt’s youngest son was running down yelling his mother was hurt. My grandparents had to carry my aunt out of the house on a blanket. She had a shrapnel wound in her stomach.

My aunt was this incredible character, despite the war she always had a smile on her face. My mam looked up to her and they made a great team. She was the leader of the pack and helped ground us with her morals and values. We were down, shelled and shot at but she gave us relief from that pressure.

When we left for school that night, we said bye to her like she would be there forever.

The doctors battled to save her the entire night, but because of the international embargo they didn’t have the equipment. She was pronounced dead at 4 am the next day. Aunt Emina was 38 when she was killed. When we left for school that night, we said bye to her like she would be there forever. You never think that you won’t see them again, we thought she would be fine because of her character and her strength. She was fearless.

As a child going through that you don’t believe humanity exists in the world. My mam didn’t get a chance to mourn her sister’s death in Bosnia. It would have been easy for my mam and grandparents to turn around and say all Croats are evil, but they didn’t. They told us good and bad people exist everywhere, resist and don’t become hateful and angry like them and that our faith tells us not to hate. They actively did that and it had a huge impact on our lives. We are still processing everything that happened during the war and hate can consume you, but my mam and grandparents freed me from the hate. The pressure to hate isn’t there.

Soon afterwards, we got news my dad was going to the UK. I didn’t know where it was, so I started looking for it on a map and we found a tiny island. At the time the UK Government in Britain was working with international agencies to relocate refugees. My dad was taken to Newcastle, he had no choice where he went. He was promised that we would be reunited with him immediately when that didn’t happen, he wrote a letter asking to be sent back to Bosnia. The local MP got involved and started campaigning for us to join him. Through letters, we got information the Red Cross would come for us.

We were only given 2 hours to pack up before the Red Cross came to get us. We knew we were going to meet my dad, but we had mixed emotions. On one hand, we were excited to go but we were leaving our grandparents in this ruined shell, but they urged us to go. We only managed to grab some basic things before the car arrived.

We spent 1 month in a Croatian refugee camp before flying from Zagreb to an immigration centre in Newcastle. The North East had links to Bosnia because Bosnian miners had sent aid to the miners in the North East, so when the war started in Bosnia, miners from this region organised and sent aid to Bosnia.

Even when arriving in a safe place, the experiences and trauma of war stay with you. Often people are left to process this while also trying to understand and navigate a new country and its systems. It is not an easy process and when refugees arrive in other countries they are often met with contempt and misguided beliefs like how easily refugees can access housing. Experiencing this as a child can be disorientating and confusing, Smajo speaks about how excited he was to meet his father and the difficulties in adjusting to a new country.

I was excited to see my dad, we had both changed in the time we had spent apart. He had aged. My first night in Newcastle, I woke up screaming because I had nightmares. Up until that point my body had been in survival mode, only now was it processing the events of the previous year. We met other children in the collection centre and went on trips, it was nice but when the honeymoon period ended, we started missing our friends and family.

I didn’t know any English and when I finally started school, I hated it, I just wanted to go back. I remember the teacher asking me to count up to 10 and everyone clapped. It was frustrating, obviously I could count to 10. In Bosnia, we used to do Maths without a calculator, this was easy.

People think refugees are given these incredible homes but it’s not like that. Our house in Bosnia was bigger and we struggled to navigate the systems in the UK. My parents started learning English at a local college and piecing our life back together. My parents didn’t know how to navigate the system and we had to ask for help when we were applying to schools and universities. We only got indefinite leave to remain in 2002, it was a long time to be living in insecurity.

When I first came to the UK and for a while afterwards, I didn’t identify as a refugee and a lot of my closest friends didn’t know. At the time the only foreign children at school were Bosnian. I was the only one in my year, so I had to integrate more. It was much harder for classes with 2 or 3 Bosnian students. The British children had picked up on what was happening in Bosnia through TV and they used to say ‘hyper, hyper, Bosnian sniper.’ I never had that. I am Caucasian, I wasn’t visibly different. I got less abuse and definitely no racial abuse, people even thought my name was a nickname. I never spoke about being a refugee, but I was conscious of being foreign and different.

The UN placed sanctions on Bosnia, the UK was also part of those sanctions, and my family members were killed because of those sanctions. The international community passed sanctions which stopped us from defending ourselves, Bill Clinton admits this in his memoirs. Even, John Major favoured not bombing the Serbs. If they had intervened, they could have stopped the fighting, but their mandate wasn’t to stop the fighting. It was to observe. If the international community didn’t want to intervene, they should have at least allowed us to arm ourselves and defend ourselves.

Genocide requires the concentrated effort of people, the media and institutions. We constantly relive what happened in Bosnia. I never told my parents I was planning to start doing talks and telling people about my experiences and the war in Bosnia. In the beginning, I used to reject TV and talks because I didn’t want my mam watching it and stressing out. She understands the importance of what I am trying to do and how it forms part of seeking justice. Hate and prejudice come from genuine fear, I want to humanise history.

Instead of being met with compassion and understating, the current media and political rhetoric surrounding refugees are divisive and hostile. They are compared to swarms and invaders intent on stealing jobs and opportunities and are portrayed as being ‘incompatible with European Values’. We asked Smajo how he felt about this current rhetoric and whether it has improved or gotten worse since the 90s.

Refugees are portrayed as being ‘incompatible others’ or actually, and the war in Ukraine has proven this, Middle Eastern, brown and Muslim refugees are portrayed as the ‘incompatible other’. Croat and Serb nationalists portrayed and continue to portray the Bosniak Muslims as non-European, as the other incompatible with European values. But what are European values? The first time I heard this term was from Croat nationalist extremists, politicians, war criminals and fascists. People that committed the biggest atrocities on European soil since the Holocaust. From people that now openly celebrate the killing of innocent women and children. Are those European values? If they are, then no, Bosniak Muslims are not compatible with these values because this isn’t what we do.

In parts of Bosnia under Serb and Croat nationalist control, war criminals are openly celebrated – the people that killed and raped members of our families, streets carry the names of war criminals and fascists from the 1990’s and 1940’s, fascist flags can be seen everywhere, and murals and monuments of war criminals are openly displayed. Serbia protects war criminals as does Croatia, and let’s remember that Croatia is an EU member state. If these are European values then no, as a refugee and as a Muslim, these aren’t my values, I am not compatible. The Bosnian government was the only side in the war that didn’t have official policies of ethnic cleansing, whereas the Serbs and Croats did. We didn’t destroy churches, synagogues, museums, and libraries.

As refugees, we have to work so hard to be accepted, but we’re still dehumanised.

I am still reflecting on what it means to be a refugee, but now I am speaking from a place of privilege and I’m frustrated. As Bosnian refugees we received a lot of support from the people in Newcastle, it was a place where we could integrate and where we were allowed to be Bosnian and Geordie. It’s gotten worse now, we had a lot more support even in terms of being allocated housing, but that support has dwindled now. As refugees, we have to work so hard to be accepted, but we’re still dehumanised. During COVID-19, people fought over toilet paper, but they still question refugees who want to find safety for their children?

Peace isn’t the absence of war, it’s the steps we take to stop war. Refugees are dehumanised in similar ways across the world, but people need to realise they are human beings. We need to change the perception and recognise their bravery and courage; they love their children so much they are willing to put them on a boat knowing they might not make the journey, just to give them a better life. When you see the media coverage of the channel crossings, those people have been travelling for months trying to seek safety but you’re only seeing a snapshot of their journey and of their lives. When you live through that, there is a thirst to do well and to continue to laugh and live.

~Smajo Beso~

To learn more about the Bosnian Genocide and to hear more from Smajo and other survivors about their experiences, please visit the Bosnian Genocide Educational Trust (BGET). BGET can also be found on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.